Riding the Sweetness Curve

As a still nerdy scientist at heart, finding an interesting graph with real impact on my day to day work was exciting. Still more fun was that it was a graph you could taste. I’ve been on a long journey through the world of sweeteners, both artificial and natural. Let me take you on a short version through how and when those can be used in your products.

I’m not going to touch on the effects of non-nutritive sweeteners. That’s its own essay. Nor is this a critique of any specific blend of sweeteners or methods. I hope this helps put words to the sensations you feel in your mouth when you taste different sweetener systems.

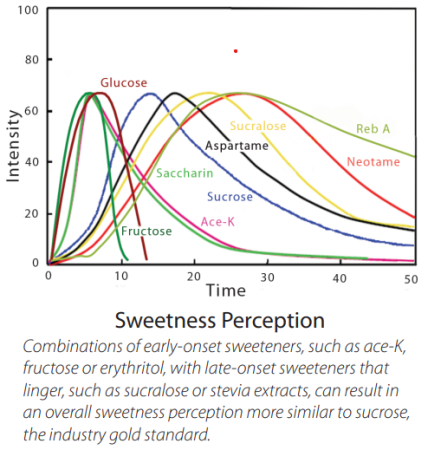

The graph above really helped me to understand and put words to the experiences i was having as I communicated with our formulators over the years whose job was to take my functional formulas and make them taste good. With some sweeteners, you’d get this instant and intense sweetness which dropped away really quickly. With others you’d get these lingering sweetness notes that were just “off” somehow.

Then of course, there was the king: Cane Sugar, or sucrose. Something deep down in our biology recognises the taste of sugar for what it is: calorie dense, and therefore good for our bodies millennia ago when calories were scarce.

What makes it so good for using in food and drinks is that it really coats your mouth, and the sweetness it brings is “full bodied”. It’s there for the duration of the taste experience, throughout your mouth, even with some pleasant lingering memory that you had something sweet.

If you look at the graph again, you see how the perception of sweetness lingers with a long tail for the sucrose curve (blue one). This graph only measures one dimension of the taste: sweetness intensity, but it’s a good proxy for how sugar is tasted when compared with the other options.

Graph from: https://www.foodincanada.com/features/sugar-reduction-in-beverages-a-fluid-approach/

Non-nutritive sweeteners

If you haven’t been living under a rock the past decade, you’ll be aware that “zero sugar”, “sugar free” etc. have been taking over. The sweeteners that help you achieve zero sugar claims usually break down into 3 buckets: artificial sweeteners, non-nutritive natural sweeteners and sugar alcohols.

Artificial Sweeteners

These have been around a long time.

Sucralose

Ace-K (Acesulfame Potassium)

Aspartame

Saccharin

Non-nutritive Natural Sweeteners

These tend to be a bit newer, and come from an originally natural source. Make no mistake though, there’s a fair bit of processing in order to make the final product. It seems the FDA regulates this similarly to the flavor world.

Stevia (Reb-A)

Monkfruit Extract

Allulose

Sugar Alcohols

Erythritol

Xylitol

Maltitol

Sorbitol

Mannitol and more

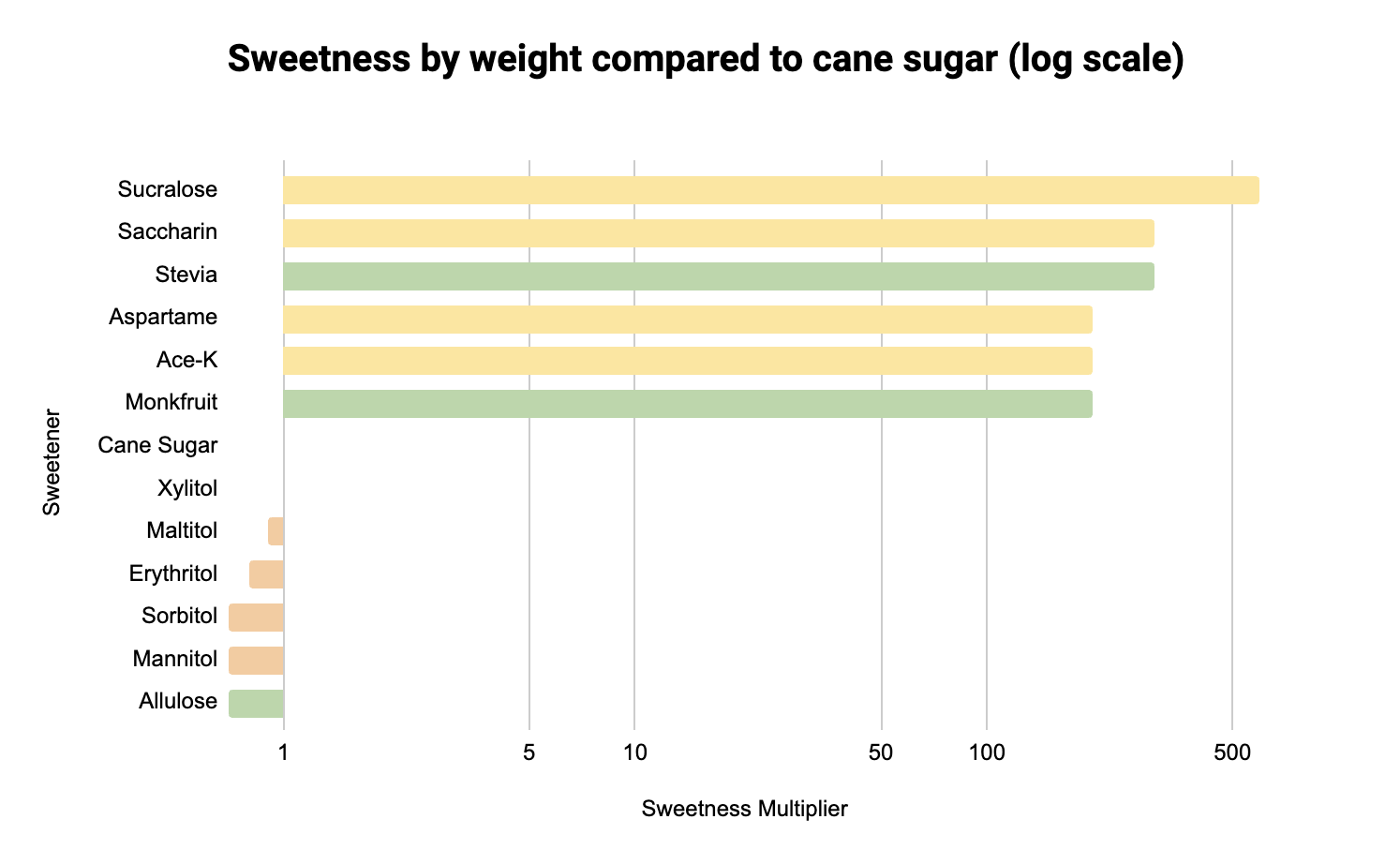

The way these sweeteners sweeten things is almost universally different from cane sugar. It’s like our brains know there’s something up with these and we’re not getting the goodness (i.e. caloric density) that we get with real sugar. Here’s a quick chart of their relative sweetness to Cane sugar. Colors just group them together: green is natural, yellow is artificial, orange is sugar alcohols:

One of the big downsides with non-nutritive sweeteners is that they often have bitter notes in the after taste, which can be hard to mask.

The challenge for food scientists and formulators is to try to match the sweetness curve that our brain associates with sugar, while hiding the off-notes that come with some of these sweeteners. Often you’ll see a blend of sweeteners used in order to achieve this.

Allulose is an interesting one. It’s a newer sweetener (first FDA Generally Regarded As Safe [GRAS] status was in 2012) that has 70% of the sweetness of sugar, but only 10% of the calories. The way it’s regulated in the USA allows you to label zero sugar despite that there are some calories in there. It’s not currently allowed in Europe or Canada.

In my experience, it is the closest mirror to sugar I’ve found: a really nice rounded sweetness without any negative aftertastes. For some reason (and if you know why, please shoot me a note), when I mix it into hot drinks, it doesn’t seem as sweet. But in baked goods, colder drinks and other applications it’s a damn good sugar alternative.

My second favorite of the natural sweeteners is monk fruit extract, a pure one without any sugar alcohols. Monkfruit is derived from a literal fruit, but also goes through some processing steps to get to the little white powder we use for manufacturing. I’ve worked with a fantastic formulator who grew up in Asia, and to him monkfruit doesn’t taste just “sweet”, it actually tastes of the fruit that he tasted growing up. Never having had that experience most of us perceive it as sweet with something slightly off when compared to sugar. It’s an intense peak right as soon as it hits your tongue, but falls away quickly.

Not everyone likes monkfruit though. Same deal with stevia. Usually the pushback here is a taste issue rather than health concerns as many consumers have with artificial sweeteners.

Cost

When designing products, eventually you always end up dealing with cost. This is where the best intentioned founders sometimes break their resolve and move to the cheaper, more artificial sweeteners. Allulose and monk fruit are the most expensive sweeteners you can get, by far. If you switch to stevia you can save a lot of money, and if you switch to sugar alcohols and/or artificial sweeteners your cost of goods gets significantly better. This is where you’ve got to know who you’re building for. If you want to hit the Natural Channel and customers in that “healthy” segment of the market, you’ve got to go natural, and take the cost hit that comes with that. You can also probably charge more to cover your costs as these consumers will pay up for non-artificial ingredients.

What I’ve discovered over the years is that the loudest people on the internet will be in your comments regardless of what decision you make.

Pick a natural sweetener? “Screw you, you picked the wrong one, I hate monkfruit!”

Pick a sugar alcohol? “Don’t buy this, it will give you colon cancer!”

And full artificial? “GROSS. Artificial ingredients…”

Oh and simple cane sugar? “SUGAR IS POISON!!!!!!”

You can’t win everyone over, so it’s better not to try. Pick your customer, and then make them insanely happy. Don’t worry about the haters.

A masterclass in this is David bars. They basically realized that the whitespace in an otherwise crowded protein bar market was to make the macros insane, and make the bar taste great. The people who were in the macro-maxxing category would pick the bar for that reason. That was more important to them than whether the sweetener was artificial or natural. That’s who they built for, and look at that story, it’s been blowing up. They did start out with a more expensive sweetener blend that included allulose but pivoted along the way. Allulose can be tricky to work with (ask your food scientist about the Maillard reaction) and that likely played a role, but I would bet they also realized that their core customer represents the majority of Americans, and they could improve their margins if they made the switch.

So what should you do?

There’s no right answer to which sweetener you should pick. You should be factoring in how important the sweetener is to your products value proposition, how important it is to the consumer, the trends in sweeteners and the cost of them. Then stick to your guns - you can’t please everyone!